In-depth Written Interview

with Bryan Collier

Insights Beyond the Meet-the-Author Movie

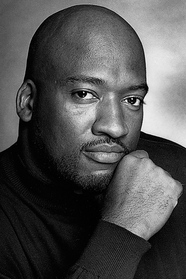

Bryan Collier, interviewed in his studio in Harlem, New York on October 8, 2001.

TEACHINGBOOKS: When did you realize that you were an artist?

BRYAN COLLIER: I started sort of late as an artist. I suppose growing up I was interested in art and had an artistic eye, but I never put it into motion until I was about 15. And something clicked in me overnight. What happened was I started with watercolors. That's the only thing that I could afford supply-wise. And I just began painting and drawing, and I've never stopped since then.

I was involved in a congressional competition during high school, and I was selected to represent the state of Maryland. I believe it was a still-life painting of flowers. And what happened was the painting hung in the capitol rotunda for a year as a winner of one of these contests. And there I met kids from all over the country who are artists, and this expanded our lives and minds to see that other kids were doing the same thing and sharing the same interests.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you end up living in Harlem after going to art school at Pratt Institute?

BRYAN COLLIER: Well, Pratt is located in Brooklyn. During college, I started a volunteer program at the Harlem Hospital, a painting studio for kids. That sort of brought me to Harlem every day, and eventually that job turned into a paying gig. I became the director of the Harlem Horizon Art Studio, which is a studio located within the hospital that's open to the children of the hospital as well as the community kids to engage in painting – not so much as a formal way, but an opportunistic way where they could paint and express themselves without instruction or without interference from me.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What are you trying to accomplish at the Harlem Horizon Art Studio.

BRYAN COLLIER: The freedom of being able to create without judgment was the true backbone of the program because what it does is allow a person to paint and listen to one's own voice instead of being influenced by my sensibilities about art. It turns one to focus on their own sensibilities because eventually, if you want to create something, it has to go back to, "what is it that you're really trying to do?" And no matter what anybody thinks or asks about it, you have to learn to trust yourself.

I came to that understanding because all through college I never knew why I was an artist. I never knew what this really meant to "be an artist." It was always a disconnect as to what it is that we do in terms of creating something. What is your intention? Why is it that one says, "This art is better than that art"? It's like saying, "Your feelings are better than my feelings" or "Your thoughts are more important than my thoughts." What is this really about?

It never really connected until I watched a child paint – when they're just totally free. And in that you see their inhibitions are gone. It goes directly to the visceral nature of creating. It went directly to the soul of why we create. In watching children do anything — in that you'll see the purest form of intention.

TEACHINGBOOKS: How did you come to be involved at Harlem Hospital's Horizon Art Studio?

BRYAN COLLIER: It had just opened six months before I got there. And they were looking for someone to volunteer to help with the program. The children I encountered were kids that were in the hospital for various reasons, whether it be gunshot, asthma, a broken leg, or whatever. And we found that the kids that were injured the most seriously had a real necessity to express what they were going through.

The community kids who aren't in the hospital need to be here, too, because they need to see both sides of the coin. The hospital is a major institution in the community, and most people go to the hospital when they're sick. Yet if you had kids you go to school with come up to paint in your hospital room, come up to paint with you three days a week or four days a week, it sort of brought some of what you're missing from not being in school into your hospital stay. So it normalized a lot of things.

What it did is it got me into the core of Harlem, because I locked in with the children of Harlem — thousands of children because I was in the school systems too, recruiting kids by telling them our program is free. You don't have to pay for anything. It's the perfect situation for an artist because you have a place to paint. We're on the seventeenth floor with a view of the City. We can see Jersey, the Bronx, Queens, all from the studio. It's all windows, natural sunlight. The painting supplies are free. You can do whatever you want with your painting. If you want to give it as a gift to somebody in your family, do that. No restriction. You come and go, you don't have to come a certain amount of times. And the door stays open because, what we found was the children — young painters — needed some sort of stability or something like a lighthouse or a staying power that will be there on a consistent basis.

Phenomenal paintings came out of the studio while I was there. I mean, we've toured around the country. Many galleries sold books of the kids' art for thousands of dollars. The kids got fifty percent of that. And it was just a wonderful time.

It was a wonderful, growing place for myself as an artist because it erased a lot of misconceptions about who an artist could be or what you could be as an artist. All you have to do is develop you, as a person. Painting and creativity is about living. It's not about the skill or the hand/eye coordination or the balance of color and composition. It's your life, it's your temperament on how you judge and see the world and act in the world. You can't hide yourself when you get into painting. You're wide open.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Is it scary for kids doing art to be that open about themselves and who they are?

BRYAN COLLIER: No, it's not scary at all. It's what they actually want. They yearn to be seen because most of the time as a child they have been pushed away. They rarely get a chance to express who they are. Children yearn to be heard.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What about the mural project you worked on in Harlem?

BRYAN COLLIER: In Harlem, I've painted thirteen murals with kids, whether it be in the parks or the playground, or even in their schools. And the same approach as we did with self-taught painters in the art studio applied to the murals. The only difference is everybody's watching because you're outside in the park. And this is a test to trust the formula of just starting the painting and letting it evolve. And you don't know what the end's going to be, with everybody watching you do this.

But what it did was, it allowed the children to dictate what their environment looked like. They painted the park. They had their name on the park. They were in the parks more than anybody else anyway. It was their park. It empowered them because five years later they could walk by that same park and see their name up. That's an incredible sense of empowerment.

Art is part of how to empower someone, whether it be painting, acting, whatever, because they get a chance to hear their own power and see it manifest. That's an incredible feat. And the murals are successful. They're still up. They're featured in movies. It's been an incredible ride.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What is the mission of your work?

BRYAN COLLIER: The important thing I want you to see is the fact that we're connected, whether I'm talking to you or whether I'm talking to any child in any classroom at any time. What I'm going to get you to see is that we're connected. And we're connected closer than you think we are as a human race. Whether you be an artist or doctor, you're still connected because we're doing the same things. And emotions and feelings and ideas that you have, I have the same ones. Even your fears are some of the same.

Art is a vehicle to bridge that connection, to let you see that we're on the same path. We are so close that it's almost mind-boggling how much we're connected.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What do you share with kids when you walk into a classroom?

BRYAN COLLIER: When I walk into a school, the first exercise I do with them is I ask them to stand up and tell me about their day as it is at this moment. And they say a range of things. "Well, I don't really feel well today," or "I feel great because I'm in the midst of this great artist." But then I want to go deeper. I say, "Well, I want you to stand up and tell me how you feel at this moment." And then I ask the whole class to watch this person talk. Watch him or her say it. Because what happens is, as kids in classrooms, we never get to hear each other talk or tell our stories. What I want them to do is focus on what it means to tell a story. And when they are loosened up and are relaxed enough to tell a story, and I don't care what it is, just say it, then we talk about how do we tell stories with books. I explain to them it's important because, when a person stands up in front of his or her class and tells a story about themselves, they're blessing the class with truth and honesty. And that goes further than the actual curriculum that you're going to get in a class.

And then we talk about the collage as a metaphor. What is a collage? It's bringing these things together.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Your mother was a teacher. Did any of her favorite books impact you?

BRYAN COLLIER: My mother was a Head Start teacher and we had all kinds of books that she would bring home. I'm the youngest of six. I wouldn't read the books. I would only look at the images. I would let the image tell me the story through all the books. And some of my early books that we had were Whistle for Willie, Snowy Day, Harold and the Purple Crayon and Where the Wild Things Are. Those were the four books that I could look at over and over growing up. They were my stories.

And the magical thing about Harold and the Purple Crayon was you never knew what he was going to do with it. You could look at it today and you still don't know what exactly he's going to do with it. And that's the dynamic that I love about creating children's books. And, for me, that would be my perfect book, if I could get you to look at a book that I do and you cannot tell what I was going to do from one page to the next. No matter what the story says, you don't know what he's going to do or you don't know how he's going to get there. And in the books that I've done thus far I've had glimpses of it, but it hasn't happened from beginning to end. So that's what I'm chasing on one level with the books, to be able to do that: to tell a story with that kind of energy.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Why did you start creating children's books?

BRYAN COLLIER: The main motivation for my doing children's books is that I have an affinity for kids, and older folks actually. I span those two generations. And one of the biggest reasons is that I believe in 1995 I went into a book store, into the children's section, and I saw books that didn't look or feel or sound like me or my kids or my people. So that sort of sparked the idea that I could probably do this if I ever got a shot. So that's what I worked towards. I said, "Some day I'm going to do a book. And I'm going to do a book not for my own self-gratification, but I'm going to do a book and I'm going to tell stories. I'm going to tell my story or explain the world as I see it, basically. But I'm going to be really honest. I'm not going to hold anything back. And I'm going to see if they're ready for it." And they are.

My second gig I did These Hands. I was speaking with one of the editors, her name is Andrea Pinckney, and she said, "We're really excited about you doing this book, These Hands, but what I urge you to do is to take a chance with every image that you do." And she said, "Take at least one chance in the book." And that just sort of lit me up because I was like, "Okay, I'm going to take every chance. Every image is going to be a chancy one." And when I say "taking a chance," I mean just being as honest as you can be about a situation in the book. Say exactly what you want to say – your first gut reaction about how to tell the story. And that's what I've done ever since, and that's the way I feel about it no matter what the subject matter is.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Describe the relationship between the pictures and the words in your books.

BRYAN COLLIER: My approach when it comes to the actual text and the images is something that I did when I was a kid. When I read a story or hear a story being read, I would always go off on a tangent visually. I would take the character and do something else with it while I was reading it, making two story lines happen at the same time.

For each of my books, I do a photo shoot before I create the illustrations. I use either family or friends to pose for me. I put regular people in it without any acting ability and have them act it out. And I take pictures of the scene as told in the text. This gives me some gestures that are important to sort of illuminate the idea of the scene.

The two people, Isaac and Sara in Freedom River, they're married. So I asked the pastors of my church to be part of my photo shoot. By having them do this adds to the drama because everything is brand new and rich and alive with something that I could never think. So I open up the area for creativity on their part. And that adds to what I'm looking for. I may do 10 rolls of film and I pick out the shots. I can see the whole book right there. And I pick out every shot that I think works.

TEACHINGBOOKS: What is Freedom River about in your opinion?

BRYAN COLLIER: Freedom River is about the power of prayer but it is never stated it in its text. In every situation that we find ourselves in, somebody prayed for you. No matter what happened, somebody prayed for you. Even though you did not know, people have been watching you ever since you were born. They hovered around you, whether they have been your angel or somebody praying and looking over you. And in the most horrific situations of the world, people are praying.

For this time of slavery, the text never really touches on prayer at all – that's part of what I brought to the book because I know that's what happens. Whether you can read or write, you can pray, and praying is about understanding that there's a higher power in the world than you. There's something outside of you, and that's part of what Freedom River was. It wasn't just a river that ran through everybody's faces. The lines that sort of indicated the river itself showed a key to freedom. When the river froze up, nobody could get through. When it thawed out, that's how they got through to freedom. The text didn't say it, but when you put yourself in that position, then all these things make sense. The river that flows through all of us is what connects us.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Martin's Big Words (a 2002 Caldecott Honor Book) is a great collaborative work. Was it difficult to express the essence of someone who has been drawn and written about so frequently?

BRYAN COLLIER: The way Doreen Rappaport put the text together was truly amazing. Initially when I read the text it had a rhythm. It almost had a drum beat under it. I could hear it. I could hear it. And my biggest apprehension was, Martin's been done a million times. He's been written about, shown with images that I've seen a million times. So my challenges were, what is it that hasn't been shown? What is it about Martin that hasn't been said thus far in the way that I want to say it?

In my church, we have a mini-cathedral — a Baptist church in Brooklyn. I think the style is neo-classical, and that means that it has within the elevations linear qualities that go up to give you a heavenly feel. That's part of the elevation ground plan of that sort of structure. And we have these great church windows that tell biblical stories. And that was the key. A stained glass window telling the story of Martin Luther King. The stained glass window acts as a metaphor also. A glass window. You see in and see out. See colors in, see colors out. So, part of Dr. King's philosophy was to bring all colors together. So we brought them together.

A lot of the scenes in the text were surrounded around the fact that he was a reverend, a pastor of a church; his Christian belief and how that belief manifested into something that was greater for the world that moved outside the boundaries of the structure of his church and spread throughout the world. This is how we told the story, from the perspective of this man as a human being, and the enormity of the pressures of just being him.

We talk and we think about the pressures that we have in life. Imagine having the whole Afro-American community depend on you. Everything that you do or don't do is on you. And then, say, in this turbulent time, I'm going to take on the posture of being non-violent in this so-violent world. And you know our gut reaction is, we have kids, we have a wife, we have families, we want to protect them. Somebody throws something through your window, blows up your house, your brother's house — killing folks, your friends, your people on a daily basis, this is the hostile South. Hatred running deep and overt. And yet you take on the power of being non-violent and sharing all those words about attacking hate with love.

The most critical thing that I wanted to stress with this book was, if you look at Martin Luther King's background, he was middle class, well-educated, with his own church. He said, "You know what? I'm going to give all this up and I'm going to die for you." And that's what he did. He didn't have to do this. He could have said, "you know what? Listen, I'm well-educated, I'm traveled a little bit. I've got my own church. I can just stay in this comfort zone here." Because a lot of people didn't really want him to do what he did. He had oppositions on all corners, whether you be white, black, or whatever. Because everybody was scared.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Martin's Big Words has no title on the cover, just a picture of Dr. King. And it is exceptionally striking.

BRYAN COLLIER: The cover from Martin's Big Words was one that came as a gift, truly. It was the last piece that we actually did for the book. I had looked at some images of Martin, but they had all been done. They'd all either been put on other covers or you've seen them. And then I came across a photograph of him, a black-and-white photograph, of him smiling. And that one was it. That was the one. And what I did was I painted him in watercolor and collage. And then I put a veil over, a thin layer of design over his face that harkens back...

The place that the cover takes me is his speech about having been to the mountaintop and seen. He knows we're going to get there, and that image is about knowing, whether he gets there with us or not. But he knows we're going to get there.

"Freedom," "peace," "together," "I have a dream," and "love" are the big themes, so they are sort of boldly placed in the book to sort of reiterate these are Martin's big words, big themes, big ideas that he had to sort of crystallize and encapsulate everything, his whole body of work. There are more, but these are the ones that we could fit in this particular text.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Uptown appears to be a tour of Harlem. Would you describe what you were trying to show in that book?

BRYAN COLLIER: That was the book that I had to write as well as illustrate. In Uptown there are images about living in Harlem, such as the idea of waking up in the morning and hearing the Metro North. Outside your window are sounds – the train or a bus or whatever. These are definitely things that are kid-friendly. There are also themes in that text for adults, such as the fact that he woke up on the Harlem River and ended up walking across town to the Hudson River. So, if you live in New York, you know it's on the other side of town. It's on the west side as opposed to the Harlem River being on the east side where the Metro North eases over. Both for kids and adults it's a tour of Harlem.

And it's more than just a pretty book. It touches on a lot of different things. It mentions the VanDerZee photographs. If you're an adult, then you know about VanDerZee photographs in Harlem and how they depicted Harlem's regular people. It sort of documented Harlem of the 20s, 30s, 40s and 50s. And, we also touched on the dynamic that happens in the barbershop. Kids and adults can relate to that. That's like a fraternity. So, it's a balance between the Harlem of old and the Harlem of today. It sort of merged both generations, so to speak, in that text.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Young people who are writers and poets can relate to Visiting Langston. What makes this a story you wanted to help tell?

BRYAN COLLIER: The thing about Langston here is that he spoke to you on every level, every stage of your life. And it didn't matter whether you were schooled or not, he spoke to the human experience that he observed and traveled and saw.

And the glorious thing about Visiting Langston is about this little girl who sort of has that old soul feel. She's an old soul and mature beyond her years in a lot of subtle ways. And you can hear it in the text. If you listen closely to the text you can hear her maturity in the text. That's why it's for adults and kids.

The words and the images speak to the idea that in life you're going to be sad and joyful. Like let's talk about New York today at this moment. [Less than one month after the terrorist attacks of 9/11/01.] I feel good. I'm still sad. There's duality that happens. Yes, the day goes on. It's a beautiful blue day out here today. But, there's an undercurrent out here, man, that's incredibly sad. So the duality is that they can happen at the same time. And that's part of the complexity of Langston. Langston's friends thought he was the happiest man alive. All they saw was him smiling and being joyful, but inside he was dealing with this. And that's part of what comes out artistically in his writings.

There are two things happening. He's misunderstood. He doesn't fit anywhere. He doesn't fit in his house; he doesn't fit in any particular space. No matter where he goes he feels uncomfortable. Even growing up as a kid when he hung out with a lot of Russian kids and stuff, he didn't quite fit in there.

The dichotomy I had with that book was, Langston . . . I mean, I've read a lot of his stuff and I credit Langston a lot for teaching us all about Harlem and making us know, hey, there's this incredible vibrant spot here. And let's never forget that. And he wrote out of fear and sorrow, and you even see in the book that he's sad, that his poems and writings are sad. When I look at this "contemporary Langston," (the girl) I see no sadness in her.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Describe what a typical workday is like for you.

BRYAN COLLIER: Well, the average day is I have a trainer that I work out with about 8:30 in the morning. We do weight training and fitness and aerobic exercise. So I get back here about almost ten o'clock. And from that I begin sketches or try to find pieces of collage I could use. And around about one or two o'clock is when I actually get into the act of painting. And that'll go on an average to maybe six o'clock in the evening, or if it's really good or really flowing it may go until ten. And around ten, between ten and twelve o'clock, I'm sort of arranging for the next day. What images I need, what collage pieces I need. And it sort of happens like that.

TEACHINGBOOKS: Where do you get your collage pieces?

BRYAN COLLIER: I use old magazines that I buy here on the street for like $1.00. Back issues of Architectural Digest and Elle magazines, fashion magazines, because they have the greatest shots of patterns. Elle magazine used to have a section of recipes, so they do blow-ups of food, which is beautifully shot. And in that I would see like outfits. Like I saw a picture of a barbecued chicken up close. That was like the greatest jacket that you can imagine.

TEACHINGBOOKS: You often refer to "blessings" in your life and work. Can you share something about this?

BRYAN COLLIER: Blessings are important when you truly recognize them and not take them for granted. A lot of things in the world are taken for granted. And in this day, in New York, in America, we took freedoms and flying and all kinds of stuff for granted. And then you realize how blessed we are and how blessed we've been when something happens. Not even necessarily as tragic that has happened in recent weeks [September 11, 2001], but as one of my pastors said in church one Sunday, "If you have never experienced or seen a miracle, just touch the person next to you because what we go through personally to get us from one point to the next is absolutely a miracle." When we recognize all these small miracles in our lives, we start to embody and appreciate what blessings really are. And the little things that we do in the world, whether it be talking with kids about children's books or whatever, you're blessing them.

And when a child looks at me, I almost break down in tears. I'm in awe of children because they're so wondrous. They're absolutely magnificent. And all the power and glory and the life that radiates through them, and that's what I thank them for. They thank me for the books and the stories, but I thank them for just their very being, their wonder. That's what blessings are.

This In-depth Written Interview was created by TeachingBooks.net for educational purposes and may be copied and distributed solely for these purposes for no charge as long as the copyright information remains on all copies.

Questions regarding this program should be directed to info@teachingbooks.net